When we talk about "generations," what exactly do we mean? Is it merely the passage of time from parent to child, a simple biological fact? Or is there something deeper, a collective spirit forged by shared history and culture? The truth, as we’ll explore in this guide on Defining 'Generation': Biological vs. Sociological Perspectives, lies in understanding both. While biology gives us a starting point, sociology adds the rich, complex layers that truly shape who we are and how we interact with the world around us.

For centuries, "generation" primarily referred to lineal descent—a parent-child relationship, a biological step in the family tree. But as societies grew more complex, and especially in the wake of rapid industrial and social change, the term began to evolve. It transformed from a simple biological marker to a powerful lens through which we understand societal dynamics, cultural shifts, and the ebb and flow of human experience.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways on Generations

- Biological vs. Sociological: Biological generations are about lineage (parent-child). Sociological generations are about shared experiences and collective identity.

- Social Constructs: Sociological generations are not just age groups; they are defined by unique historical, political, and cultural forces during formative years.

- Karl Mannheim's Influence: This sociologist introduced "generational consciousness" and "fresh contact," explaining how shared experiences shape worldviews and drive social change.

- Dynamic Boundaries: While cohorts are often defined by 15-20 year ranges, their boundaries are fluid, and experiences can vary widely even within a single generation.

- Why It Matters: Understanding generations is crucial for academia, business strategy, HR management, and fostering community cohesion.

- Meet the Cohorts: From the resilient Builders to the digitally native Generation Alpha, each cohort brings distinct values and perspectives shaped by their unique historical context.

Beyond Birthdays: The Core Difference

Before diving into the complexities of "Boomers" and "Zoomers," let's clarify the fundamental distinction between the two ways we think about generations. It's a foundational understanding that underpins all further discussion.

The Biological Lens: Simple Succession

At its most basic, a "generation" is a biological succession. Think of your family tree: your grandparents, your parents, you, your children. Each stage represents a new generation, a direct line of descent. This definition is straightforward, concrete, and typically spans about 20-30 years, reflecting the average age difference between a parent and their child.

This traditional view sees generations as an unbroken chain, where life simply passes from one individual to another. While undeniably true in a genealogical sense, it doesn't account for the why behind evolving societal values, different approaches to work, or the changing political landscape. It's a timeless concept, but it's also incomplete for understanding societal shifts.

The Sociological Lens: Shared Shaping Forces

This is where the concept truly comes alive. In sociology, a "generation" isn't just a group born around the same time; it's a social construct. It's a cohort of people born within a specific timeframe—typically a 15-20 year window—who share profound, formative life experiences. These aren't just any experiences; they are unique historical events, technological breakthroughs, cultural shifts, or major societal conditions that indelibly stamp their collective identity, values, and worldviews.

Imagine growing up during a war, the dawn of the internet, or a global pandemic. These aren't just isolated events; they color perceptions, shape aspirations, and influence how an entire cohort navigates adulthood. Sociological generations provide insight into the continuity and discontinuity of social life, showing us how society both evolves and holds onto certain patterns across time. It’s about how historical moments become personal experiences that, collectively, define a group.

The Architect of Generational Thought: Karl Mannheim's Legacy

To truly grasp the sociological perspective, we must acknowledge Karl Mannheim. His seminal 1928 essay, "The Problem of Generations," laid much of the groundwork for modern generational theory. Mannheim wasn't just observing age groups; he was exploring how different age cohorts develop distinct ways of experiencing and understanding the world.

The Power of "Generational Consciousness"

Mannheim argued that generations aren't just passive recipients of history. Instead, they actively develop a "generational consciousness." This is a shared awareness and understanding among individuals in a cohort, forged by their common socio-historical conditions. It's not about every single person thinking exactly alike, but rather sharing a similar potential for experience and a common outlook on the world's problems and possibilities.

Think of it like this: A major event—say, the invention of the smartphone—doesn't just happen to a generation; it becomes part of their collective "DNA." It shapes how they communicate, learn, shop, and even think about privacy. This shared context leads to similar interpretive frameworks and responses to social change, differentiating them from cohorts that came before or after.

"Fresh Contact": The Engine of Change

Another profound contribution from Mannheim was the concept of "fresh contact." He suggested that as each new generation enters society, they confront existing cultural materials, social norms, and institutions not as a given, but with fresh eyes. They haven't been as deeply entrenched in the established ways of thinking, allowing them to reinterpret the world in novel ways.

This "fresh contact" is crucial. It challenges the status quo, questions established norms, and often introduces new values and approaches. This process isn't always smooth; it can lead to intergenerational conflict as new ideas clash with old ones. However, it can also foster intergenerational cooperation, as older generations adapt to new perspectives and younger generations build upon past achievements. Ultimately, this dynamic interplay is a powerful driver of social evolution and innovation.

Why Generational Analysis Isn't Just Academic Theory

Understanding generations might seem like a niche academic pursuit, but it's a mainstream field with profound practical implications for nearly every facet of contemporary society. The insights derived from generational analysis are vital for navigating our increasingly complex, multi-aged world.

- For Sociology and Academia: It's the bedrock for analyzing societal evolution, understanding social movements, and examining the intricate web of individual and group relations across time. It helps researchers predict future trends and interpret past behaviors.

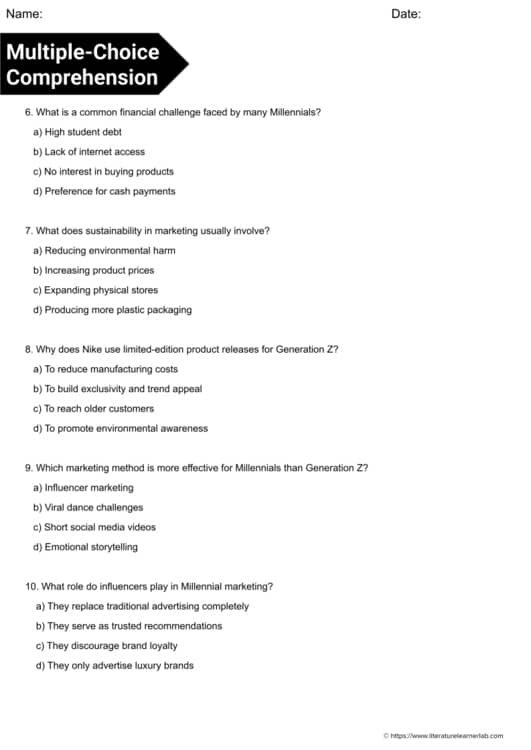

- For Businesses: In today's diverse market, knowing your customer means knowing their generation. Businesses leverage generational insights to understand, engage, communicate with, and build products and services that resonate. Ignoring generational differences can lead to irrelevancy, while embracing them opens doors to tailored marketing, innovative product development, and stronger brand loyalty.

- For HR, Leadership, and Management: The modern workplace is a multi-generational melting pot. Effective leaders must understand the distinct values, communication styles, and motivational triggers of each cohort to foster effective intergenerational cohesion. This means empowering diverse groups, resolving potential conflicts, and creating inclusive environments where everyone can thrive. It’s about tailoring management strategies to harness the unique strengths of each generation.

- For Community Cohesion and Personal Understanding: Beyond the professional realm, generational analysis helps us bridge gaps in our personal lives and communities. By appreciating the unique strengths and perspectives shaped by different historical contexts, we can foster understanding, empathy, and respect across age divides. It helps us see why a grandparent might value thrift, a parent might prioritize work-life balance, and a younger person might champion social causes, making our interactions richer and more harmonious.

Understanding the Rhythm: How Long Does a Sociological Generation Last?

Unlike biological generations, which have a fairly consistent span, the duration of a sociological generation is a topic of ongoing discussion and, at times, contention. However, there's a general consensus that helps us delineate these influential cohorts.

A sociological generation is typically defined as a cohort born within a specific timeframe, usually around 15-20 years. This period is chosen because it's long enough for significant historical events, technological advancements, or cultural shifts to profoundly impact a group during their crucial formative years (childhood and young adulthood).

It's important to recognize that while these definitions are incredibly useful, their boundaries are often fluid and can be debated. For example, a Baby Boomer born in 1946 might have quite different experiences and perspectives than one born in 1964, even though they share the same generational label. The world simply changed a lot during those two decades, impacting their formative years differently. The same fluidity applies to Millennials (1981-1996) or any other cohort.

Historically, the term "generation" evolved from describing all living people at one time to its biological definition, and then, significantly, to its sociological application, now commonly spanning approximately 15 years. This understanding of timeframes is crucial for defining the specific cohorts we see today, helping us grasp how long does a generation last and what factors influence its duration.

Meet the Cohorts: A Guide to Contemporary Generations

Let's put theory into practice by exploring the major generational cohorts in contemporary society, noting their defining characteristics and the formative experiences that shaped them. Keep in mind that these are broad strokes, and individual experiences within each generation will always vary.

The Builders (or Silent Generation) (born 1928-1945)

- Defining Era: Grew up during the Great Depression and World War II, followed by post-war reconstruction.

- Core Values: Thrift, resilience, strong work ethic, loyalty to institutions, respect for authority, sacrifice for the greater good.

- Impact: They literally built much of the modern society, its suburbs, institutions, and infrastructure. They navigated immense hardship with stoicism and a sense of duty.

- Perspective: Less likely to challenge authority publicly, they valued stability and security above all. Often understanding, adaptable, and appreciative of younger generations' differing approaches.

Baby Boomers (1946-1964)

- Defining Era: Shaped by post-war prosperity, the Cold War, and significant social upheaval (Civil Rights Movement, Vietnam War, feminist movement, environmental movement). Their label comes directly from the post-WWII baby boom.

- Core Values: Optimism, individualism, social justice, activism, personal fulfillment, challenging the status quo (they were the "social justice warriors" of their time).

- Impact: Played a crucial role in expanding higher education, the labor market, and driving economic, housing, and infrastructure booms. Initiated profound cultural, social, and economic change.

- Perspective: Often seen as "the bank of mum and dad," supporting subsequent generations. While celebrated for their activism, they are also sometimes criticized for contributing to environmental degradation and economic inequality.

Generation X (1965-1979/1980)

- Defining Era: Came of age during a period of shifting societal norms, rising divorce rates, the AIDS epidemic, and the early digital revolution. Often called the "latchkey generation." Douglas Coupland's novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture gave them their name, representing an anti-establishment, somewhat cynical mindset.

- Core Values: Independence, resourcefulness, self-reliance, skepticism towards institutions, work-life balance (more than Boomers).

- Impact: Many secured property ownership earlier than subsequent generations and benefited from economic prosperity pre-COVID-19. They embraced small business and entrepreneurial opportunities, achieving significant economic establishment.

- Perspective: Often seen as a bridge between the Boomers and Millennials, they value pragmatism and directness. They prioritize results and competence over hierarchical structures.

Generation Y (Millennials) (1980-1994)

- Defining Era: Grew up with the internet and mobile technology, but also experienced major global events like September 11, 2001, which shaped their global outlook during their formative years. Faced the dot-com bust, the 2008 financial crisis, and accelerating house prices coupled with flat wage growth.

- Core Values: Tech-savviness, collaboration, diversity, social responsibility, purpose-driven work, experiences over possessions.

- Impact: The first "digital natives" to truly integrate technology into all aspects of life. Many are now entering parent and family life stages, redefining traditional family structures and work patterns.

- Perspective: Known for specific cultural preferences and a desire for immediate feedback and progression. Often criticized for being entitled, but equally celebrated for their idealism and desire for impact.

Generation Z (1995-2009)

- Defining Era: The first generation to grow up entirely in a post-9/11 world, deeply shaped by ubiquitous internet access, social media, and the COVID-19 pandemic during their formative years.

- Core Values: Digital fluency, pragmatism, diversity and inclusion, financial conservatism, authenticity, resilience, strong desire for homeownership.

- Impact: Highly adaptable, value education, lifelong learning, and up-skilling in a competitive environment. They work hard, volunteer at higher rates, and are more likely to work for non-profits, focusing on values, fulfillment, and making a difference.

- Perspective: Often described as more mature, cautious, and globally aware than previous generations due to constant access to information and exposure to global challenges.

Generation Alpha (2010-2024)

- Defining Era: The first generation fully born in the 21st century. Shaped by the rapid advancement of technology (e.g., Instagram and iPad launched in 2010, around their birth year), increasing globalization, and ubiquitous connectivity.

- Core Values: Digitally immersed from birth, personalized learning, global citizenship, adaptability, creativity, comfort with AI.

- Impact: Navigating a wholly new societal landscape where AI, augmented reality, and seamless digital interaction are norms. They are often seen as "mini-influencers" and active participants in digital culture.

- Perspective: Likely to be the most technologically integrated, self-sufficient, and globally interconnected generation yet, potentially redefining education, work, and social interaction.

Generation Beta (2025-2039 - Predicted)

- Anticipated Traits: While still in the realm of prediction, Generation Beta is anticipated to be even more technologically integrated, curious, and to highly value diversity, change, and difference, reflecting and amplifying current societal trends.

- Future Context: Their formative years will be defined by ongoing climate challenges, advanced AI integration, potential space exploration, and further blurring of digital and physical realities.

Navigating the Nuances: Challenges and Misconceptions

While generational analysis is a powerful tool, it's not without its pitfalls. A nuanced approach is essential to avoid oversimplification and foster genuine understanding.

Stereotyping vs. Understanding

The biggest danger of generational labels is their potential to devolve into stereotypes. Calling all Millennials "entitled" or all Boomers "out of touch" not only dismisses individual differences but also shuts down productive dialogue. Generational labels are meant to be frameworks for understanding broad trends and shared influences, not rigid boxes that define every single person. The goal is insight, not caricature.

Fluid Boundaries: Not a Hard Line

Remember, generational birth year cut-offs are somewhat arbitrary. They are useful markers, but life doesn't suddenly change on January 1st of a new cohort's start year. The experiences that define a generation unfold gradually, and people born on the cusp of two generations (sometimes called "cuspers") often share traits from both. Thinking of boundaries as fuzzy rather than fixed helps us maintain flexibility in our analysis.

Internal Diversity: Not Everyone Is the Same

Even within a single generation, there's immense diversity. Factors like socioeconomic status, race, geographic location, gender, and individual personality play a huge role in shaping a person's experiences and values. A Gen Z growing up in rural America will have different formative experiences than one in a bustling global city, even if they share some broad generational traits. These intersectional differences are crucial and should always be considered.

The Danger of Over-Simplification

Reducing complex societal issues solely to "generational gaps" can obscure other important factors like economic inequality, political ideology, or cultural background. While generations offer a valuable lens, they are one piece of a much larger puzzle. It's vital to integrate generational insights with other sociological and economic analyses to get a truly comprehensive picture.

Harnessing Generational Insights: Practical Applications

Now that we've explored the definitions, theories, and cohorts, how can you practically apply this knowledge? Understanding generational perspectives isn't just for academics; it's a powerful skill for anyone looking to connect, lead, or innovate.

For Leaders and Managers (HR)

- Tailor Communication: Recognize that some generations prefer face-to-face, others email, and younger cohorts might favor instant messaging or collaborative platforms. Adapt your style to maximize clarity and engagement.

- Customize Motivation: Understand what drives each generation. Builders might value stability and recognition for loyalty. Boomers might seek impact and respect for experience. Gen X often prioritizes autonomy and work-life balance. Millennials thrive on purpose and development. Gen Z seeks authenticity, strong values, and clear career paths.

- Foster Mentorship: Create formal or informal mentorship programs that encourage knowledge transfer and reverse mentorship. Older generations can share wisdom and institutional knowledge, while younger generations can offer fresh perspectives on technology and new trends.

- Review Benefits & Perks: What attracts and retains one generation might not appeal to another. Consider flexible work arrangements, professional development opportunities, health and wellness programs, and social impact initiatives.

For Marketers and Businesses

- Segment Your Audience Wisely: Move beyond simple demographics. Use generational insights to craft messaging that resonates with specific values, aspirations, and communication preferences of your target cohort.

- Product Development: Consider how different generations interact with technology, what problems they face, and what they value. For example, products emphasizing sustainability might appeal strongly to Gen Z, while convenience and reliability might be key for older generations.

- Channel Strategy: Where do your target generations consume information? Traditional media for some, social media for others, and new platforms constantly emerging for the youngest cohorts. Optimize your presence where your customers are.

- Brand Storytelling: Craft narratives that reflect the historical context and values of your target generation. Show you understand their journey and speak their language.

For Community Builders and Personal Growth

- Promote Intergenerational Dialogue: Organize events or initiatives that bring different generations together to share stories, learn from each other, and collaborate on community projects. This is crucial for bridging gaps and fostering understanding.

- Challenge Your Own Biases: Use generational knowledge to reflect on your own assumptions about others based on their age. Ask yourself: "How might their formative experiences have shaped this perspective?"

- Practice Empathy: When you encounter differing viewpoints or behaviors, instead of immediately judging, try to understand the generational context from which they might arise. This cultivates patience and deeper connections in families, friendships, and wider community interactions.

- Leverage Strengths: Recognize that each generation brings unique strengths to the table. Older generations offer experience, stability, and historical perspective. Younger generations offer innovation, adaptability, and fresh insights. Together, they create a stronger, more vibrant whole.

Your Turn: Bridging the Generational Divide

Understanding "generation" isn't just an academic exercise; it's a vital tool for navigating our diverse world. By appreciating the difference between biological succession and sociological shaping, by grasping Mannheim's powerful ideas, and by familiarizing ourselves with the distinct yet interconnected cohorts that populate our society, we equip ourselves to build stronger relationships, more effective organizations, and more cohesive communities.

The real power of generational insights lies not in labeling or categorizing, but in fostering empathy and communication. It’s about recognizing that while we may walk different paths forged by different times, we all share the human experience. As you move forward, challenge your own assumptions, seek out diverse perspectives, and actively work to bridge the generational divides. The future, after all, belongs to all of us, together.